Bucking Brain Death is a Threat to the System

the Jahi MacMath Case

Written by Helen Stanton, Chapple, PhD

Difficult topics such as cardiac death vs. neurological death and end of life care are some of the ethical issues in healthcare examined in Creighton University’s Bioethics master’s program. In the following article, Helen Stanton Chapple, PhD, Associate Professor within Creighton’s Department of Interdisciplinary Studies examines the ethical issues surrounding the diagnosis and subsequent care of 13-year-old Jahi McMath.

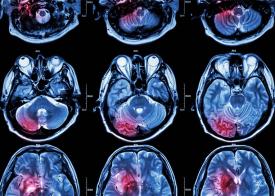

Jahi McMath suffered anoxic brain injury at 13 and was declared dead by neurological criteria in 2013. Her family refused to accept the diagnosis and worked with her for next 5 years. They posted videos of her following commands. Neuro experts who examined her during this time believed the original diagnosis was accurate, but that it did not persist (Lewis 2018). She suffered cardiac death by liver failure in 2018.

Besides the extraordinary idea that brain death may not be irreversible, the case raises ethical questions regarding power and race. All are important topics, worthy of exploration. But here we consider the idea of bucking a declaration of brain death and point to the significance of the McMath’s family’s success at doing so.

To declare death is to attest officially that an ontological change has taken place, one of profound social disruption. Partly to restore order and protect well-being, the group asserts its authority over individual survivors when one of its members dies. It imposes mandatory procedures regarding body removal and disposition, as it urges conformity to post-death cultural norms.

Governments appoint those allowed to attest to the fact of death and oversee the civil processes that follow, often using proxies such as physicians and medical examiners. We bow to the bureaucratization of death, accustomed to the idea that the state affirms who is alive and who is dead, issues death certificates, and oversees medical investigation into “wrongful death.” This is a strong and seemingly incontrovertible social power.

The ontological changes to the person’s body rendered by cardiac death are so obvious that such state and social power over death is unmarked. But when death by neurological criteria occurs, the usual signs confirming the ontological change are missing or muted. Breathing is supported, the heart beats, and the skin is warm. The mismatch between death and the patient’s robust appearance is so deeply counterintuitive that the social power to declare death is at risk. Compliance with the norm is deeply ingrained, however, and most people obey its dictums. Jahi’s family rebelled.

In moving Jahi secretly to New Jersey, the McMaths thwarted the medical and legal establishment. They were strongly denounced and stigmatized for their efforts (Paris, Cummings, and Moore 2014). Why did they suffer such visceral condemnation for making what seemed like a personal decision? Their actions threatened the very fabric of society by insisting that a dead person be treated as if she were living, thereby taxing (putting stress on) the general understanding of death and its “normal” aftermath, and taxing (literally) the social medical system.

A closer examination reveals dissension in the ranks. Controversy persists regarding labels for devastating neurological conditions, even with the Uniform Determination of Death Act (President’s Commission 2008; Truog 2018). The McMaths’ pushback highlighted a disagreement among the state-sanctioned authorities. The judge refused to order the hospital to withdraw life support despite the diagnosis and state-issued death certificate. (Paris, Cummings and Moore 2014).

This case offers several levels of liminality: individual rebellion against recognized social authorities; categorical questions involving neurological diagnoses; and medical, legal, and judicial officials who failed to enact agreed-upon social norms. The McMath family drove a truck through these liminalities and liberated their daughter. Their courageous defiance illustrates that the state’s ability to declare who is alive and who is dead may be especially vulnerable in the domain of devastating neurological events.

Helen Stanton Chapple, PhD, RN, MA, MSN, CT

Professor

Creighton University’s Bioethics programs

References

- Lewis, A. (2018). Reconciling the Case of Jahi McMath. Neurocrit Care, 29, 20–22.

- Paris, J. J., Cummings, B. M., & Moore, M. P. (2014). “Brain Dead,” “Dead,” and Parental Denial: The Case of Jahi McMath. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 23, 371–382.

- The President’s Council on Bioethics. (2008). Controversies in the Determination of Death: A White Paper by the President’s Council on Bioethics. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/death/

- Truog, R. D. (2018). The 50-Year Legacy of the Harvard Report on Brain Death. JAMA, 320(4), 335–336.